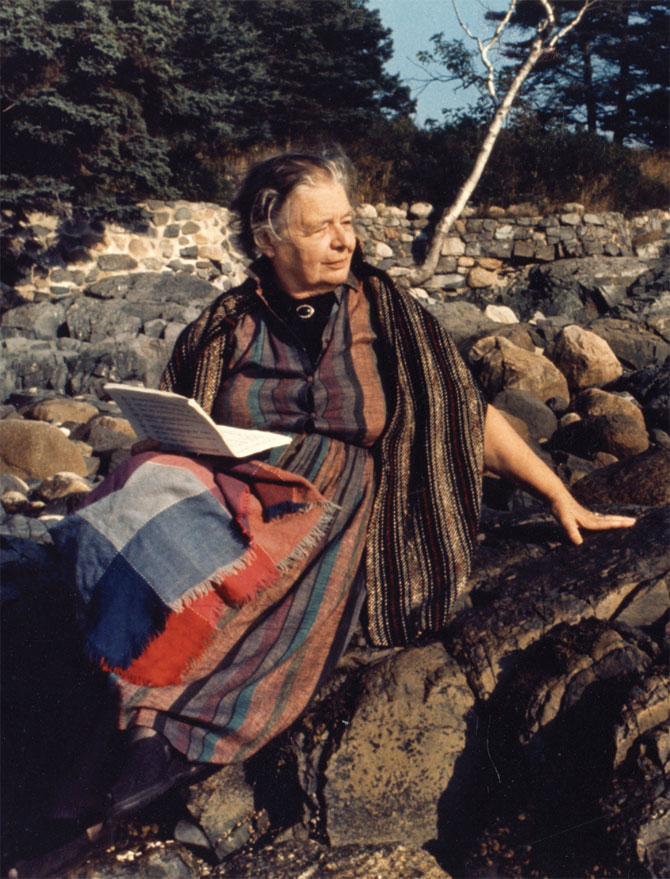

POETRY MONTH 30/30/30: Inspiration, Community, Tradition: DAY 25 :: Ana Bozicevic on Marguerite Yourcenar

disclaimer, from Ana: “if you need a word about why I am featuring a novelist as a poetic influence; her work is poetic to the point of absurdity.” et alors…

disclaimer, from Ana: “if you need a word about why I am featuring a novelist as a poetic influence; her work is poetic to the point of absurdity.” et alors…

—

I, YOUrcenar.

None of my friends seem to give a shit about Marguerite Yourcenar. Sure, someone’s father read her in the 80s—probably Memoirs of Hadrian—and there was an interview in the Paris Review with her just then—just at her death. Naming her as an influence has been taken at times (dans mon cas) as an affectation. {This is supposed to be personal, so I’m making it so. But what isn’t? There’s no person, so person’s everywhere.} So this is what I can tell you about Marguerite Yourcenar & “I” (“L’être que j’appelle moi”/the person I call myself, as she puts it):

That

– it was my father who introduced me to her. And started me toward owning most of her books.

– “I” passed her novella of incestuous love, Anna Soror, around my Croatian high school like the mind-porn that it sure was.

– “I” translated parts of her Fires, a reimagining of antique myths—especially the one about Sappho—and made an offering of them to a young woman. This was my idea of courtship; should’ve read Plato’s Lysis first.

– when “I” had a blog for four years, called Quoi? L’Eternité. it was named thus after Yourcenar’s memoirs, not Rimbaud. She also introduced me to Yukio Mishima.

That’s enough now. But from a current vantage, it’s incredibly ironic that Yourcenar’s writing should have served as a queer f-to-f offering – considering the fact that though she quite likely was queer, she was also very oblique about it – what I’ve heard called “old school.” Here’s a passage from that Paris Review interview cited here without value judgment – neither for Yourcenar nor her interviewer and his “deviance:”

INTERVIEWER

One striking aspect of your work is that nearly all your protagonists have been male homosexuals: Alexis, Eric, Hadrian, Zenon, Mishima. Why is it that you have never created a woman who would be an example of female sexual deviance?

YOURCENAR

I do not like the word homosexual, which I think is dangerous—for it enhances prejudice—and absurd. Say “gay” if you must. Anyway, homosexuality, as you call it, is not the same phenomenon in a man as in a woman. Love for women in a woman is different from love for men in a man. I know a number of “gay” men, but relatively few openly “gay” women. But let us go back to a passage in Hadrian where he says that a man who thinks, who is engaged upon a philosophical problem or devising a theorem, is neither a man nor a woman, nor even human. He is something else. It is very rare that one could say that about a woman. It does happen, but very seldom; for example, the woman whom my father loved was very sensuous and also, in terms of her times, an “intellectual,” but the greatest element of her life was love, especially love for her husband. Even without reaching the high level of someone like Hadrian, one is in the same mental space, and it is unimportant whether one is a man or a woman. Can I say also that love between women interests me less, because I have never met with a great example of it.

INTERVIEWER

But there are writers, like Gertrude Stein and Colette, who have tried to illuminate female homosexuality.

YOURCENAR

I do not happen to like Colette and Gertrude Stein. The latter is completely foreign to me; Colette, in matters of eroticism, often falls to the level of a Parisian concierge.

[That was a sick burn. And then later]:

[very well, she contradicts herself]: I think that an intelligent woman is worth an intelligent man—if you can find any—and that a stupid woman is every bit as boring as her male counterpart.

[and]

But what is love? This species of ardor, of warmth, that propels one inexorably toward another being? Why give so much importance to the genitourinary system of people?

~

… My, but I do love a curmudgeonly old bitch. The conflict, the contradictions of these statements are not only piquant, but deeply moving. Yourcenar was most certainly the intellectual equal of her renaissance-men protagonists (who are most often scrupulously amoral), and yet she had the horror of the feminist movement. The fires of desire in her books are so vivid as to incinerate their own stylization. The notion of this first female member of the Académie française, oft-celebrated for her neoclassical craft, enacting over the oeuvre of many novels a complex drag is nothing if not postmodern. Recent research – which, to admit, I have only just begun to look at – reassesses her in terms of contemporary literary theories as a writer of the subversive neobaroque. In the words of Natalie Barney, perhaps all this virtue is simply a demand for greater seduction.

I would advise you simply to read Yourcenar. But if you want a pointer, here are two:

O YES! Read Fires.

ARE YOU IN LOVE?

HELL NO! Read An Obscure Man.

Moi, I am in love with An Obscure Man. This novella traces the life of an anonymous man named Nathanaël who travels from the Amsterdam of Rembrandt and (as Yourcenar tells it) “becomes shipwrecked off the coast of Maine in America, marries a girl who dies of TB, travels back to England and Holland, marries a second time a woman who turns out to be a thief and a prostitute, and is finally taken up by a wealthy Dutch family.” Nathanaël dies of TB at 28, alone on a Dutch island where he is gamekeeper. It’s the most beautiful death I’ve ever read. This anyman’s profound resistance to the acquisition of culture(s), and his simultaneous ability to partake of what’s most precious to them, offers the template of a kind of classless cosmopolitanism that’s absolutely liberating.

Here’s a passage on Nathanaël the servant listening in on the music in the house of his employers:

“Nathanaël, in livery on those occasions, admitted the visitors, who seemed literally to glide across the carpets; the music imposed a silence before it had even begun.

In the pantry, listening through the door, the young valet tried to suppress as much as possible the clatter of the silver. Then, all of a sudden, it would rise up like an apparition, heard but not seen. Up to then, Nathanaël had known only tunes inseparable from the voices that sang them…But here it was something else.

Pure sounds rose up (Nathanaël now came to prefer those which have not undergone an incarnation, as it were, in the human throat), then subsided, only to mount higher and dance like flames of fire, but with a delicious freshness. They embraced each other and kissed like lovers—except that such a comparison was too corporeal. They might almost have seemed serpent-like, had that not suggested too sinister an image; like clematis or convolvulus, except that the delicate coils of sound did not seem that fragile. Yet they were fragile: a door carelessly slammed was enough to shatter them. As the questioning and answering between violin and cello, between viola da gamba and harpsichord, took place, the image of golden balls falling step by step down a marble staircase suggested itself, or that of fountains melting into one another in the basins of a garden like the ones Mijnheer van Herzog had described having seen in Italy or in France.”

Golden balls indeed. Yeah, I love this writer, love this woman.

Here is a baroque prose poem [of Ana's] that reminds me [er, her] of "Fires." It appeared a few years back in the Bat City Review.

Callas Regrets

Though X won’t call, with each first light his name dawns first, before my name,

and squats on the cool floor to pet the terrier Sleep. I lie abeat, all in a sweat—

this is hard work! to bend the bars of bones and fit him in. What is a friend?— our

song went. Now I’ll tell: he’s an army to be welcomed, over and over, with song.

Even when through the unmanned South one sole drunk sentry wanders in: his

name… This hole I wedge it in was made to fit only my voice. So, it’s my whim

to die! As my dog loves me through neglects, although her time’s a short red leash,

I don’t mind waiting here for X. See: since he makes me wait, he must think me

immortal!

Ana Bozicevic is the author of "Stars of the Night Commute," translator, and co-editor of esque and the PEN Poetry Series. At The Graduate Center, CUNY she aspires after knowledge.

[Editor’s note: Both Ana, and a dog, are a landscape. When listening to her read at the Chapbook Festival (which she co-founded and co-runs, tirelessly), I learned that she “dreamed she was a drop of sweat” … and it was somewhere around that moment where I came to truly appreciate all the facets of this particularly brilliant prism of a woman/poet. My goodness. And it’s organic, too: the poems and thoughts and efforts, and, you know, just a little ditty on Yourcenar, like she says, just dripping off like the sweat of dreams. You cannot help but smile reading or knowing Ana, she reminds you that it’s human, and ridiculous, and a good deal of fun, even when we’re up to our knees in the mud of the thing. I’m so grateful she took a moment to share her words with us.]