6th ANNUAL NAPOMO 30/30/30 :: DAY 21 :: C.K. Hugo Chung on Ha Jin (哈金)

[box][blockquote]HAPPY POETRY MONTH, FRIENDS AND COMRADES!

For this, the 6th Annual iteration of our beloved Poetry Month 30/30/30 series/tradition, I asked four poets (and previous participants) to guest-curate a week of entries, highlighting folks from their communities and the poets who’ve influenced their work.

I’m happy to introduce Janice Sapigao, Johnny Damm, Phillip Ammonds, and Stephen Ross, who have done an amazing job gathering people for this years series! We’re so excited to share this new crop of tributes with you. Hear more from our four guest editors in the introduction to this year’s series.

Hungry for more? there’s 150 previous entries from past years here! You should also check out Janice’s piece on Nayyirah Waheed, Johnny’s piece on Raymond Roussel, Phillip’s piece on Essex Hemphill, and Stephen’s piece on Ronald Johnson’s Ark, while you’re at it.

This is a peer-to-peer system of collective inspiration! No matriculation required.

Enjoy, and share widely.

– Lynne DeSilva-Johnson, Managing Editor/Series Curator [/blockquote][/box]

[line][line]

[box]

WEEK THREE :: CURATED BY PHILLIP J. AMMONDS

Poets are fingerprints

A menagerie of textures

that leave a unique cultural-

impression on the world

The seven poets that I have the honor of curating for the week of April 16-22, are varied in tone, approach, inspiration–but all have a thundering presence that thrums the strings in your soul. They demand that you be present and feel whatever you will.

Throughout this week, readers will take a journey through waves of love, self-reflection, mourning, discovery, tribute, longing and acceptance.

To hear these poets speak life into their muses and perform their work, please come to our reading, Tribute, at Dixon Place on Monday, April 24th at 7:30 PM.

Phillip J. Ammonds, a Brooklyn native, is a founding member of the writing collective Writeous, with whom he has co-produced three chapbooks. Phillip curates Rainbows Across the Diaspora, the queer text reading series at Dixon Place in New York City. Phillip also performs his work as Trinity Rayn, Drag Poet. His work has appeared in the anthology Black Gay Genius: Answering Joseph Beam’s Call (Vintage Entity Press, 2013),HIV: Here and Now Project, Yellow Mama and The Operating System.

[/box]

[line]

C.K. Hugo Chung on Ha Jin (哈金)

[line]

When I first read Ha Jin’s breakout novel, Waiting, which won the National Book Award and the PEN/Faulkner Award for fiction in 1999, I was serving the obligatory military duty in northeast Taiwan. It was a translated copy by a local publisher. I devoured the book within a week.

The translation, not by the author himself, effectively conveyed a melancholy tale, inspired by a true event in China during the era of Cultural Revolution. Unlike many Chinese novels told in a fashion of ornate convolution, I was touched by his unfussy yet sophisticated storytelling. Afterwards, I immediately sought out the original English-language copy and discovered that his writing there was even more clear and linear. Surprised by the fact that a traditional Chinese love triangle could be told this freshly and poetically in a different language, what was more amazing to me was that Ha Jin, whose legal name was Jin Xuefei, wasn’t even an Asian American. He was born in northeast China, went to the United States in 1985 on a student visa, and launched his English literary career after the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989. His first English poem, The Dead Soldier’s Talk, appeared in the respectable The Paris Review.

English was not his mother tongue. For the next two decades, he would become a prolific writer whose publications included fictions, personal essays, poetry, and short-story collections, all written in English. It wasn’t until 2015, with the support from a Taiwanese publisher, he finally published his first and original Chinese poetry collection.

I started my writing career in 1998 with a Chinese novel. After the military service I worked for some Taiwanese local congressman as a ghostwriter for few months before starting my graduate studies at New York University in 2002. In 2007, I wrote my first English poem and since then, I gradually shifted gears in creative writing from Chinese to English. English was not my mother tongue.

I must admit over the years Ha Jin’s poetry speaks louder to me than his other creations. The intensity of him being an exile, literarily and literally, from his homeland and its long tradition, is magically palpable in his English poems. His struggle as an outsider to his own country, and an immigrant in his brave new world are best displayed in a writing which celebrates cutting off any meandering and obscure expressions. Even though they are rooted subconsciously in his cultural background. Read the below excerpt from his first English poem:

[line]

[blockquote]

Why have you brought me wine and meat

and paper-money again?

I have told you year after year

that I am not superstitious

Have you the red treasure book with you?

[/blockquote]

[line]

To me as a bi-cultural writer, the stanza strikes a delicate balance between a almost skeletal structure, and complex impressions from each object mentioned in the lines. Another stunning example in the later stanza of the same poem:

[line]

[blockquote]

Last week I dreamed of our mother

showing my medal to a visitor

She was still proud of her son

and kept her head up

while going to the fields.

She looked older than last year

and her grey hair troubled my eyes

[/blockquote]

[line]

I am convinced that a Chinese and an English reader will pick up different experiences when reading it, and that’s the magic of Ha Jin’s literary achievement. As a writer who chooses to demonstrate himself in a distinctively different literature, he is able to extract rich materials from an exotic reference to English poetry, and transform them into an accessible style, without losing too much of their original multi-dimensions. I admire his ambition and ability.

Ha Jin once said that Chinese is not only his mother tongue but also his first language, and there’s a difference between these two linguistic concepts when it’s applied to creative writing. Mother tongue, to him, is a living implementation, which can evolve under the circumstances, especially for immigrants. But using first language to creative writing will always be the most ideal. (His statement here is translated from the epilogue of his first Chinese poetry collection, Another Space.) Despite achieving one of the highest regards in American English literature, he discourages English writing for a Chinese writer. For him, to balance two unique writing traditions sucks up so much energy just to sail across that technicality ocean, and it doesn’t guarantee the creative and cultural compass will always work to a writer’s favor to maintain a high level of literary authenticity. This is where I beg to differ.

Having lived in New York City where I witnessed so many emerging poets of diverse ethnic groups who could carefreely reference and incorporate their cultural backgrounds into their literary works, it dawns on me why can’t I develop a hybrid style of writing where Chinese and English converges. Chingish, after all, has been around in the oral form for many years, amused and consumed by two readerships through multiple platforms. As a Taiwanese writer whose mother tongue is Chinese but first language is English (in Ha Jin’s term) I’ve put in years of effort to seek out the literary nirvana where two languages and traditions can be weaved harmoniously.

[line]

In my own poem, I Am Not Your Ching-Chung-Chong, I tried what I call “interpretive exposition” to strive for a nuanced delivery:

[blockquote]

Mispronounce misunderstand misrepresent missing in action

胡說 瞎說 亂說 一切都是白說

Do what you like

I will make a fuss

Call me drama queen

Isn’t that what you want me to be?

哎,人性哪!my passive aggressiveness

[/blockquote]

[line]

Ha Jin’s literary journey has always been inspirational to me, even though our intentions don’t stay on the same path. I appreciate his Chinese poetry just as much as his English one, if not even more. They are pretty similar in terms of writing style, but the emotional pungency is even stronger in his Chinese poems.

In the below excerpt from his latest Chinese poetry collection, Home On the Road, I don’t dare to translate it word by word but I would like to provide some interpretive exposition:

[blockquote]

回來吧! 二十歲的饑餓 (Come back! My hunger of a twenty-year-old)

再來占據我的身心 (Come occupy my body and soul)

再給我帶來瘋狂的純真 (Come bring me the crazy innocence)

再讓幻想在我的血脈裡湧動 (Come set imagination to scurrying in my veins)

再讓我放任的歌聲 (Come free my uninhibited voice)

穿過晨光浸滿的樹林 (Seep through the sun drenched forest)

[/blockquote]

[line]

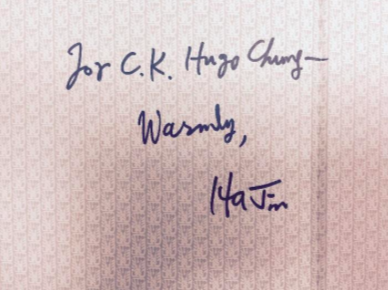

In 2017, Ha Jin appeared in Taipei International Book Exhibition to promote his latest Chinese poetry collection and English novel, The Boat Rocker; I also happened to be there for my own books.

Excited as fans, I waited in a long line to ask him, in Chinese, to sign my purchased copy of Home on the Road. I also told him that I’ve been developing a writing career as an English writer here in Taiwan, which caught his attention. He looked up, smiled at me, and signed this:

I smiled and handed him a copy of my book, Night Market. Mission accomplished.

[line]

[line]

[textwrap_image align=”left”]http://www.theoperatingsystem.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Screen-Shot-2017-04-13-at-8.05.04-PM-e1492128343906.png[/textwrap_image] C.K. Hugo Chung is Taiwanese by nature, New Yorker by nurture. Writing in both Chinese and English, his essays, poetry and short stories can be found in various bilingual publications. He is the co-founder of a NYC-based writers’ collective, Writeous, and he currently manages TWG Press, the only local English literature publisher in Taiwan. He collaborated with Taipei Writers Group to publish four anthology novellas: Taiwan Tales (2014), Night Market (2015), Peak Heat (2016) and Twisted Fairy Tales for Adults (2016).

His solo book, Writeous Accents, will be released in 2017.

For more information, please visit:

https://www.facebook.com/Writeous2008

https://www.facebook.com/TWGpress/

Instagram: @ckhugowriteous

Twitter: @Writeous1[line]

[h5]Like what you see? Enter your email below to get updates on events, publications, and original content like this from The Operating System community in the field below.[/h5]

[mailchimp_subscribe list=”list-id-here”]

[line]

[recent_post_thumbs border=”yes”]