5th Annual NAPOMO 30/30/30 :: Day 12 :: Wally Swist On Leo Connellan

[box]It’s hard to believe that this is our FIFTH annual 30/30/30 series, and that when this month is over we will have seeded and scattered ONE HUNDRED and FIFTY of these love-letters, these stories of gratitude and memory, into the world. Nearly 30 books, 3 magazines, countless events and online entries later, and this annual celebration shines like a beacon at the top of the heap of my very favorite things to have brought into being. [If you’re interested in going back through the earlier 120 entries, you can find them (in reverse chronological order) here.]

When I began this exercise on my own blog, in 2011, I began by speaking to National Poetry Month’s beginnings, in 1966, and wrote that my intentions “for my part, as a humble servant and practitioner of this lovely, loving art,” were to post a poem and/or brief history of a different poet…. as well as write and post a new poem a day. I do function well under stricture, but I soon realized this was an overwhelming errand.

Nonetheless the idea stuck — to have this month serve not only as one in which we flex our practical muscles but also one in which we reflect on inspiration, community, and tradition — and with The Operating System (then Exit Strata) available as a public platform to me, I invited others (and invited others to invite others) to join in the exercise. It is a series which perfectly models my intention to have the OS serve as an engine of open source education, of peer to peer value and knowledge circulation.

Sitting down at my computer so many years ago I would have never imagined that in the following five years I would be able to curate and gather 150 essays from so many gifted poets — ranging from students to award winning stars of the craft, from the US and abroad — to join in this effort. But I’m so so glad that this has come to be.

Enjoy! And share widely.

– Lynne DeSilva-Johnson, Managing Editor/Series Curator [/box]

[line][line]

The Art and Necessity of Festschrift: Fair Warning: Leo Connellan and His Poetry and a Review of Leo Connellan’s Death in Lobsterland

[line][script_teaser]When Leo Connellan lived in New York, he would sell carbon paper and typewriter ribbons between 8:00 a.m. and 2:00 p.m., then go the Limelight Café on Sheridan Square to write his poems. “I made it an atmosphere where I could write,” he says. “In that din and over cups of coffee, I realized time was passing me by, and that I didn’t have any excuses left for not writing. I embraced it.” [/script_teaser]

[line]

Festschrift (German pronunciation: [ˈfɛstʃrɪft]; plural, Festschriften [ˈfɛstʃrɪftən]) is commonly known as a book that honors a writer, often during that person’s lifetime, sometimes not. Fair Warning: Leo Connellan and His Poetry (Tokyo, Japan: Printed Matter, 2011), edited by Sheila Murphy and Marilyn Nelson, was both a long labored and much awaited publishing project. Connecticut Poet Laureate Leo Connellan died in 2001, and although this collection of essays and reviews regarding his work was in various stages of being assembled, and then readied for publication, the Festschrift, in tribute to him, took nearly a full decade to be fully realized as a published book.

I take delight in the honor of having been invited to contribute a review that I wrote of one of Connellan’s books, Death in Lobsterland (Fort Kent, Maine: Great Raven Press, 1978), but I am doubly honored since I was also asked to contribute an endorsement for the back cover of the Festschrift, which I considered to be a privilege, since many of the contributors to the book included such poets and writers of notoriety as the eminent and perennially charming and magnanimous Richard Wilbur.

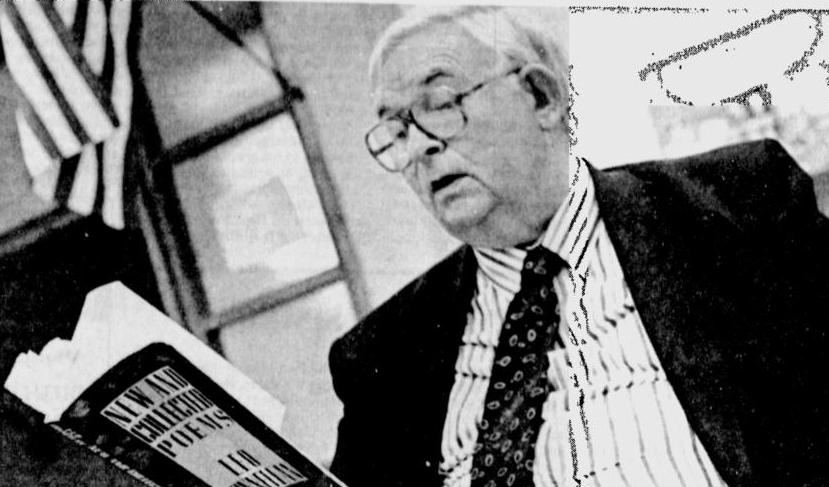

Initially, I first met Leo Connellan when I was directing a poetry reading series at The Theater and Space on Orange Street in New Haven, Connecticut more years ago now then I would like to admit. Leo Connellan was enjoying his first real literary success upon his publishing First Selected Poems in the University of Pittsburgh Press Poetry Series—and he was then in his late forties or early fifties. He was a man who lost his mother as a child; entertained visions of becoming a writer as a young man, which sprung him from a hardscrabble life in Maine, upon which he would eventually base his big American poems; hitchhiked the country and would go on to write most memorably about the experience, in an historical as well as personal context; could reminisce about seeing Dylan Thomas drink pints of stout in the White Horse Tavern in the Village; and whose very essence and being, despite being a married man and a father of a daughter, at that time, depended on poetry and the writing of it.

Leo Connellan was only the second Poet Laureate of the State of Connecticut, after the Pulitzer Prize-winning James Merrill. In opposition to Merrill’s urbanity and financial wealth and his stature in the greater literary community, Leo Connellan was a working man, albeit one who was a salesman in a white collar, and a working man’s poet. Although comparisons aside, Leo Connellan worked tirelessly during his years as Poet Laureate of the State of Connecticut in the Poetry-in-the-Schools Program. Whether it was deep gratitude of his being awarded his new status or his devout love of poetry that mattered, and probably both, his being a proponent of the written word and teaching students of all ages anywhere from grammar school to high school to college was a passion tantamount to his devotion of writing his own poetry, if not more so.

Leo Connellan’s life and his poetry are entwined. His work celebrates the human spirit as well as portraying what the editor of the periodical my review was published in chose as the headline to the piece as “Injustices of the Human Heart.” Although Leo Connellan left Maine not long out of his teens, its rocky coast and the calloused fingers and palms of its farmers and fisherman remained in his psyche and became the very ethos of his poetry which today often goes overlooked despite its largesse in the most American of senses—since it resembles, in its metaphysical girth, a symphony by Aaron Copeland or a painting by Edward Hopper. If you seek the American grain, of course you would immediately think of William Carlos Williams and his notion of composition he called the variable foot and of such books of his as Pictures from Brueghel and Other Poems, which was the epitome of his shorter lyrical poems as well as the vastness of his four book-narrative poem Patterson; whereas, with Leo Connellan his classic shorter poetry is collected in his last book, The Maine Poems and his now little appreciated masterpiece was his book-length poem, Crossing America, illustrated with woodcuts by one of the great masters of the genre, Michael McCurdy, and issued from the artist’s now legendary Penmaen Press.

To augment, and certainly to enlighten, the legacy of the poetry of Leo Connellan and his spirit, I enclose my lengthy back cover endorsement, which was only used in part on the back of the Festschrift, and then my review of one of this poet’s seminal books, Death in Lobsterland.

******

In his poem “On the Eve of Becoming a Father,” Leo Connellan writes that he “had been about to hang up” his proverbial “gun,” however “the hammer shot one spark into the moon,/ so magnificent, it is beyond me.” The poem is from First Selected Poems (University of Pittsburgh Press, 1976). That book remains a volume of lasting and memorable poems, and that is rare for any book in any genre. The author of those poems was only beginning, although well past his mid-forties, he was to eventually write and publish his best work in a series of subsequent books, often by waking at dawn, before going out into the world to make his living as a traveling salesman, to pen his poems that are cut straight from the American grain.

The poetry of Leo Connellan is a poetry of perseverance. He survived the loss of his mother as a child, and, forgoing his having completed a college degree, entered into the arena of American literature, whose territory is often enough overseen only by academics. However, his books continue to speak for themselves, and more importantly, not just for poetry, but for America herself. Connellan begins his book-length poem, Crossing America, with these autochthonous and memorable lines: [line]

[box]

We hitchhiked America. I

still think of her.

I walk the old streets thinking I

see her, but never.

New buildings have gone up.

The bartenders who poured roses

into our glasses are gone.

We are erased.

[/box] [line]

Although Connellan’s poetry has persevered beyond all erasure, like a palimpsest, Crossing America, with respect to literary achievement alone, truly belongs next to its fictional counterpart, Jack Kerouac’s On the Road.

I can still see Leo reading his poems aloud, with one hand conducting the line breaks of each verse like a conductor with a baton leading a symphony orchestra, his voice enunciating the last word of each line like a sculptor who has chiseled them out of the granite of the post-WWII American experience. Thankfully, we have his treasure trove of poems of survival: “Amelia, the Mrs. Brooks of my Childhood.” “By the Blue Sea;” “Tell Her that I Fell;’ and lesser known gems, such as “Blueberry Boy,: finding him, and us, before “the tripup of manhood,” on our collective knees

[line][articlequote]picking/ frantically with expert watered tongue,/ ignorant of what lay out of the woods.”[/articlequote][line]

Now, there is a Festschrift in his honor that is a veritable celebration of the poetry of Leo Connellan, as it is a tribute to America, and why the work of Leo Connellan is a significant contribution to American literature.

[line]

[articlequote]A poem is an anonymous gift to an anonymous recipient; and when you’re finished with it, it doesn’t belong to you anymore, it belongs to someone else. —Karl Shapiro, in a letter to Leo Connellan

[/articlequote] [line]

Leo Connellan is a poet who has weathered a fourteen year silence from writing, a bout with alcoholism, and a number of nine-to-five jobs as a traveling salesman. He portrays his home state of Maine, where the winters can be as harsh as the economy, with verbal crispness, deep empathy, and an active compassion. His poems are often funereal, tragic, and resonant. “So many of my poems are about Maine because that’s where I come from. They’re about working men, about the injustices of the human heart,” says Connellan, who at the age of fifty has just published his eighth collection of poems, Death in Lobsterland. You don’t have to come from Maine to appreciate his work. Nor do you have to be an academic to understand it, although Connellan is an exceptional craftsman. His poems lure you with their lyricism, then snap shut like a lobster trap. Take the poem “Scott Huff,” for example:

[line]

[box]

Think tonight of sixteen

year old Scott Huff of

Maine driving home fell asleep at

the wheel, his car sprang awake

from the weight of his foot head on

into a tree. God, if you need him

take him asking me to believe in

you because there are yellow buttercups,

salmon for my heart in the rivers,

fresh springs of ice cold water running away.

You can have all of these back for Scott Huff.

[/box] [line]

After attending the University of Maine, Connellan took his chances spinning around the country like a chip played on a roulette wheel. For Connellan, Maine would be a place he would always return to, that would draw him back again and again, but New York City proved to be his primary stomping ground from the mid-50s through the early 60s.

When he lived in New York, he would sell carbon paper and typewriter ribbons between 8:00 a.m. and 2:00 p.m., then go the Limelight Café on Sheridan Square to write his poems.

[line][articlequote]I made it an atmosphere where I could write,” he says. “In that din and over cups of coffee, I realized time was passing me by, and that I didn’t have any excuses left for not writing. I embraced it.” [/articlequote][line]

“My career as a writer began by what I thought writing might be,” Connellan continues. “The trick of writing is simplicity. The thing to do is edit. Once the idea is clear, get rid of excess words. Excess words reveal the writer is bluffing behind nothing to say. I don’t rush. The poem will be done when it is. But the minute you have to explain it you’re writing prose.”

Finally, Penobscot Poems was published by New Quarto Editions in 1974. Then a quick succession of books followed—Another Poet in New York (Living Poets Press); First Selected Poems (University of Pittsburgh Press); Crossing America (Penmaen Press); Seven Short Poems (Western Maryland College Writers Union); and in 1978, from Great Raven Press, of Fort Kent, Maine, Death in Lobsterland.

[line][articlequote]Writing is something you can’t help yourself from doing,” he says after his years of struggle. “It is everything to me, and I knew I could write if I didn’t die from bad luck or from drinking.”[/articlequote] [line]

Connellan is an elegist, making Death in Lobsterland his best work in many ways. “It is the book I always wanted to write,” he says. The book contains many long narrative poems such as “By the Blue Sea,” “Edwin Coombs,” and what just may be the poem he may be most remembered by, “Amelia, Mrs. Brooks of my Old Childhood”—all painful reminiscences knotted like the calloused hands of the fisherman and cannery workers that they both criticize and eulogize.

They are raw and overpowering poems, compelling rereading after rereading. They have so much life compressed in them that they throb like the ache of a lobsterman’s hands.

Simultaneous with the publication of Death in Lobsterland, the film Leo Connellan at 50 was released and aired on public and cable television. [line]

[articlequote]There are two ways that we write,” says Connellan. “Either we are born brilliant or something disturbs us.” He claims that “all good writing is realized by us because of what the writer has written for the reader to fill in. This gives us the feeling that we’ve had something to do with its accomplishment. I think this is the secret of art.”

Leo Connellan has succeeded in what he set out to do so many years ago in Rockland, Maine, his hometown, where he feels “it was an accomplishment to be born there, grow up, and leave.” [/articlequote] [line]

In his work, he fulfills his own poetic credo—writing big American poems that are worth rereading and endowing the reader with a sense that these works of art are in part their own accomplishment.

[line][line]

[textwrap_image align=”left”]http://www.theoperatingsystem.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Willimantic-Wally-Swist-Poet-2-June-24-20091-e1460409402359.jpg[/textwrap_image]Wally Swist’s books include Huang Po and the Dimensions of Love (Southern Illinois University Press, 2012); The Daodejing: A New Interpretation, with David Breeden and Steven Schroeder (Lamar University Literary Press, 2015); and Invocation (Lamar University Literary Press, 2015). His poems have appeared in many publications, including Commonweal, North American Review, Rattle, Sunken Garden Poetry, 1992-2011 (Wesleyan University Press, 2012), and upstreet. Garrison Keillor recently read a poem of Swist’s on the national radio program The Writer’s Almanac.

[line]

[h5]Like what you see? Enter your email below to get updates on events, publications, and original content like this from The Operating System community in the field below.[/h5]

[mailchimp_subscribe list=”list-id-here”]

[line]

[recent_post_thumbs border=”yes”]